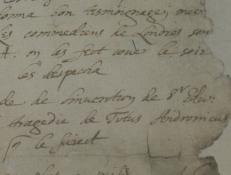

Shakespeare is first mentioned as a playwright in 1592, when he had already written at least five plays: The Comedy of Errors, Titus Andronicus, and Henry VI, Parts 1, 2, and 3. By 1598, a literary critic attributes a dozen plays to him, including one that is now considered lost, Love’s Labors Won.

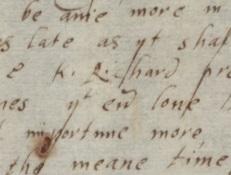

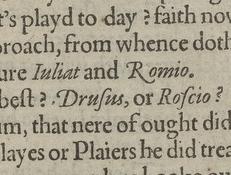

Shakespeare’s contemporaries gossiped about him, and read, saw, and responded to his plays. Evidence for Shakespeare’s prominence in the playwriting community appears in manuscript and print, including title pages, literary anthologies, and literary criticism by his contemporaries. Occasionally, we encounter more subtle glimpses of the theatrical network at work--for example, diary entries, or in one instance, a conversation with Shakespeare about a play’s author, recorded by Sir George Buc, Master of the Revels, who was responsible for censoring plays for performance in the early 17th century.

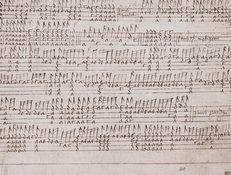

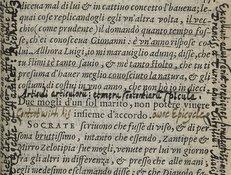

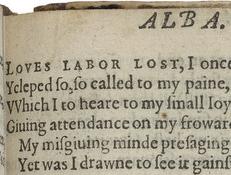

Like other plays from the period, Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be read both as stories and as sources for sententiae, passages that become stand-alone proverbs when removed from the play. Beginning in 1600, a group of editors and publishers elevated English plays to a more respectable status by excerpting them in printed literary anthologies and printing “commonplace markers” (modern-day quotation marks) alongside extractable sayings in the plays themselves. These markers would indicate passages that readers could then copy into their own commonplace books, personalized collections of proverbs.