Terms of use

Images that are under Folger copyright are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This allows you to use our images without additional permission provided that you cite the Folger Shakespeare Library as the source and you license anything you create using the images under the same or equivalent license. For more information, including permissions beyond the scope of this license, see Permissions. The Folger waives permission fees for non-commercial publication by registered non-profits, including university presses, regardless of the license they use. For images copyrighted by an entity other than the Folger, please contact the copyright holder for permission information.

Copy-specific information

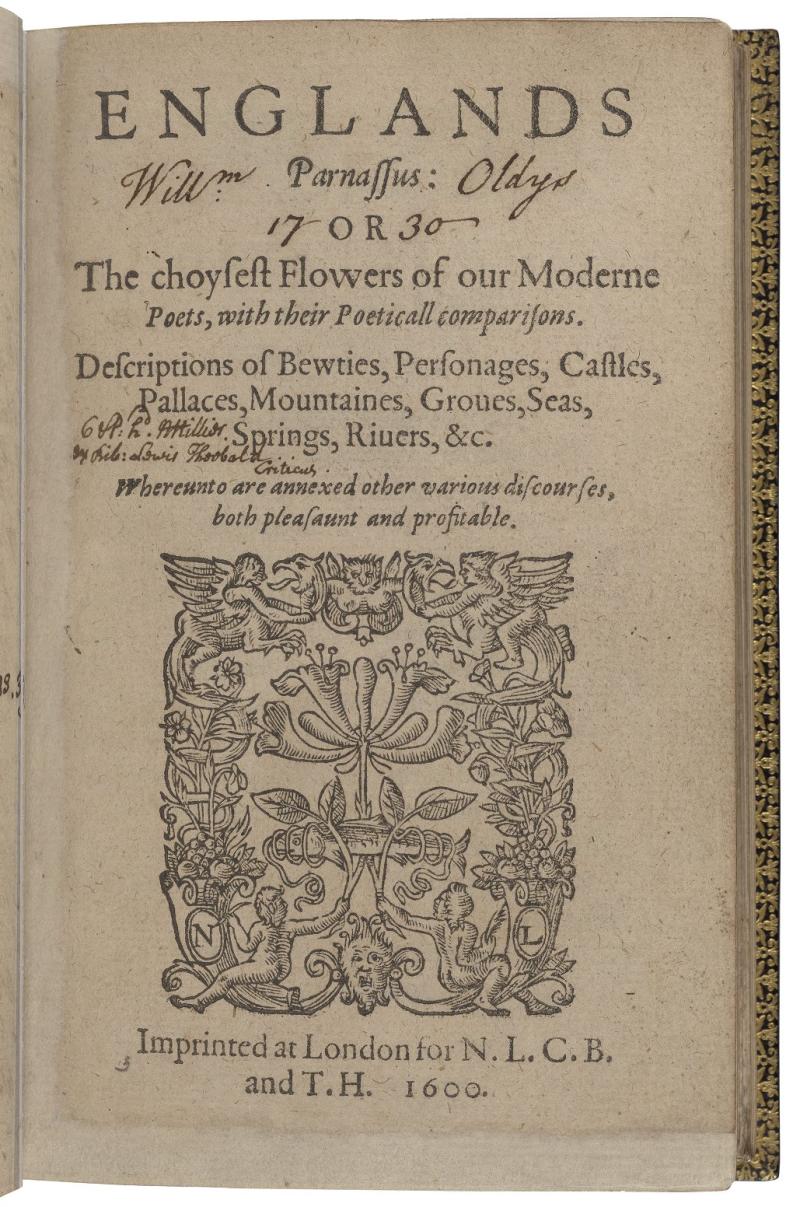

Creator: Robert Allott

Title: Englands Parnassus, or, The choysest flowers of our moderne poets, with their poeticall comparisons descriptions of bewties, personages, castles, pallaces, mountaines, groues, seas, springs, riuers, &c. : whereunto are annexed other various discourses, both pleasaunt and profitable.

Date: London : For N.L., C.B. and T.H., 1600.

Repository: Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, USA

Call number and opening: STC 378 copy 1, leaves A1v-A3r & pages 1, 3, 7, 8, 12, 14, 24, 48, 54, 55, 56, 89, 108, 109, 111. 113, 123, 124, 125, 132, 137, 143, 154, 155, 156, 157, 164, 171, 172, 173, 176, 178, 180, 182, 185, 189, 190, 191, 192, 204, 207, 217, 222, 229, 241, 246, 248, 261, 279, 280, 282, 283, 284, 286, 288, 291, 293, 297, 306, 307, 311, 313, 327, 328, 334, 348, 369, 382, 396, 407, 423, 424, 431, 432, 446, 451

View online bibliographic record

Erin A. McCarthy, "Shakespeare anthologized: England's Parnassus," Shakespeare Documented, https://doi.org/10.37078/166.

Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 378 copy 1. See Shakespeare Documented, https://doi.org/10.37078/166.

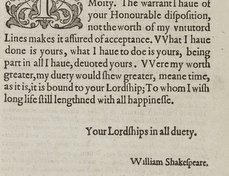

Englands Parnassus is one of two printed commonplace books, or collections of extracts organized by topic, compiled by Robert Allott, and was printed shortly after John Bodenham’s Bel-vedére. In Englands Parnassus, Allott draws together excerpts from “Modern” sixteenth-century English poetry, whereas he focused on contemporary prose works in his earlier collection, Wits Theater of the Little World (1599). As Ann Moss, Arthur F. Marotti, and others have shown, including living authors like Shakespeare in such collections marks a major shift in the status of English literature by suggesting that it was worthy of preservation and study. Little is known about Allott himself; although scholars have identified two Robert Allotts who may have been responsible for these books as well as a few commendatory verses, they do not agree as to whether these works were created by the Robert Allott of Lincolnshire or of Yorkshire.

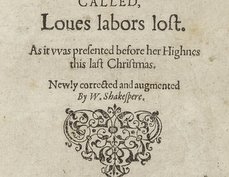

Like other plays from the period, Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be read both as stories and as sources for sententiae, passages that become stand-alone proverbs when removed from the play. In 1600, when Englands Parnassus was printed, fourteen of Shakespeare’s plays had already been printed, and Allott includes multiple excerpts from Romeo and Juliet (13 excerpts), Richard II (7), Richard III (5), Love’s Labor’s Lost (3), and Henry IV Part 1 (2). The other nine plays are not represented in Englands Parnassus at all.

Nevertheless, references to Shakespeare’s narrative poems far outstrip those to his plays. Park Honan notes that Allott “selected thirty-nine passages from Lucrece,” meaning that he “took fewer [passages] from all the author’s plays then in print” than he did from Lucrece alone (Honan, 179). Venus and Adonis is also well-represented with twenty-six selections.

Excerpts attributed to Shakespeare (sometimes incorrectly) appear under forty-seven topic headings, with the largest number, twelve, grouped under the heading “Loue,” with an additional “Loue” entry by Shakespeare added near the end of the book. Allott also includes several Shakespeare quotations for “Griefe” (5), “Feare” (4), and “Words” (3), and “Delaie,” “Kings,” “Lechery,” “Vertue, “Women,” “Mane” (morning), and “Discriptions of Beautie & personage” each garner two.

Numerous copies of Englands Parnassus survive; there are seven copies just at the Folger Shakespeare Library. This copy, Folger copy 1, was purchased by Mr. Folger, and is signed “Will[ia]m Oldys 1730.” Subsequent owners include the writer Lewis Theobald and the antiquary James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps.

Two annotators, possibly among the book’s owners, have supplemented the printed paratexts. One added a “List of the Poets” on slightly smaller leaves of laid paper inserted between the title page and the first topic heading, “Angels,” which includes an extract from Richard II. Another annotator has listed the page numbers that include quotations from Shakespeare, starting next to Shakespeare’s name in the handwritten list and continuing on the blank leaf facing the title page. For these readers, at least, Shakespeare was the most important author in one of the earliest canons of early modern English poets.

Written by Erin A. McCarthy

Sources

Estill, Laura. “Proverbial Shakespeare: The Print and Manuscript Circulation of Extracts from Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Shakespeare 7.1 (April 2011): 35–55.

Honan, Park. Shakespeare: A Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Ingleby, C.M., L. Toulmin Smith, and F.J. Furnivall. The Shakspere Allusion-Book. London: Oxford UP, 1932.

Lesser, Zachary, and Peter Stallybrass. “The First Literary Hamlet and the Commonplacing of Professional Plays.” Shakespeare Quarterly 59.4 (2008): 371–420.

Marotti, Arthur F. “Allott, Robert (fl. 1599–1600).” Arthur F. Marotti in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., edited by Lawrence Goldman, October 2006. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/413 (accessed January 5, 2016).

Moss, Ann. Printed Commonplace-Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Stallybrass, Peter, and Roger Chartier. “Reading and Authorship: The Circulation of Shakespeare 1590–1619.” in A Concise Companion to Shakespeare and the Text, ed. Andrew R. Murphy. Malden, Oxford, and Victoria: Blackwell, 2007. 35–56.

Last updated January 25, 2020