Terms of use

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, has graciously contributed images of materials in its collections to Shakespeare Documented under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. Images used within the scope of these terms should cite the Bodleian Libraries as the source. For any use outside the scope of these terms, visitors should contact Bodleian Libraries Imaging Services at imaging@bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

Document-specific information

Creator: [Samuel Radcliffe?]

Title: A common place book

Date: ca. 1622-1625

Repository: Bodleian Library, Oxford University, Oxford, UK

Call number and opening: MS. Eng. misc. d.28, pp. 355, 359 & 375

This circa 1620s manuscript commonplace book includes eleven Shakespearean extracts from four plays: three from Richard II, one from Romeo and Juliet, five from Hamlet and two from Othello. One of his plays, Richard III, was judged by the compiler “nought worthy the excerpting” (end of column 700).

The manuscript is a folio volume of 649 leaves, written in both Latin and English, and organized into columns. The first half is mostly dedicated to extracts from classical works, while the second half contains a mixture of extracts from works of theological interest and English literature, including sixty-two dramatic extracts from plays by Shakespeare, Chapman, Jonson, Fletcher, Beaumont and Dekker on pages 355 to 359, and page 375. The extracts are mostly arranged by author and play. However, the Shakespearean extracts are scattered throughout the range. The extracts from Richard II appear on page 355, Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet appear on page 359, with extracts from Beaumont and Fletcher, and Chapman interposed between the two Shakespearean plays, and finally, Othello appears on page 375.

The compiler copied Shakespearean extracts from the 1598 quarto of Richard II in columns 697-698 (2.1.5-14; 2.1.163-66; 2.2.14-17), the 1605 edition of Hamlet in columns 705-706, (1.2.150; 1.3.124-129; 3.2.69-76; 3.4.49-54; 5.2.43-47) the 1609 quarto of Romeo and Juliet in column 705 (2.2.190-195), and the 1622 edition of Othello in column 738 (2.3.380-382; 5.2.246-249).

Although the compiler states the author and source text for each classical extract, the dramatic extracts are not clearly attributed. Instead, the compiler attaches this information inconsistently to either the first extract or the second. The attributions are also sometimes encoded. Using “a variant of the so-called rotate-one Caesar cipher, named after Julius Caesar who used it in his correspondence” (Coatalen, 154) the compiler used the next letter of the alphabet while spelling the title or author’s name. Therefore, the first extract from Richard II is attributed as “UlF, Usbhfekz pg Skdibse Uif tfdpoe. cz Tiblftqf bsf” for “THE, Tragediy of Richard The second. By Shakespeare” (column 697). The attributions for Hamlet and Othello also include the title and playwright, using a mix of encoded and regular writing (columns 705 and 738 respectively). The compiler added only the title of the play for the extract from Romeo and Juliet (column 705), and did not use the code. The inconsistency of this attribution system suggests a degree of playfulness, but also perhaps an attempt at elusiveness. Perhaps the compiler was hoping to conceal this material, as the sources might have been deemed too frivolous to be found in a collection mainly dedicated to serious, theological topics. At the same time, the compiler very precisely indicates the page, format and year of publication of each play excerpted. For example, the compiler indicates “4o: pag: 84:” for Romeo and Juliet (column 705), although Guillaume Coatalen observed that “the pagination of the extract from Romeo and Juliet, as in other extracts from Shakespeare in the manuscript, does not belong to any early quarto” (155). Perhaps these paradoxically hidden but detailed entries refer to a personal collection of plays, where a new pagination was added, hence the difference from the printed pagination of the early quartos, or perhaps the pagination refers to another personal collection of extracts, as cross-referencing was often practised if compilers had several personal notebooks.

The compiler also adds Latin commentaries at the end of some extracts. For instance, “the tongues of dying men,” extract from Richard II (column 697) is labelled as “morientis hominis loquela verissima” (or “a dying man’s true speech”), simply summarizing the content of this passage. Although some comments following dramatic extracts suggest the compiler might have read and interpreted these passages in a religious context, the comments attached to the Shakespearean excerpts suggest the compiler was more interested in Shakespeare’s use of language. Perhaps the compiler recognized that “tongues of dying men” echoed Erasmus’s Latin from Encomium Moriae, or perhaps he recognized it from Englands Parnassus, where the Shakespearean passage also appears.

In general, the choice of Shakespearean plays reflects the popularity of these plays in other collections. Romeo and Juliet and Richard II were among the most popular plays in Belvedere and Englands Parnassus (both published in 1600); Edward Pudsey also excerpted from the same Shakespearean plays in his manuscript collection (circa 1600-10), while Abraham Wright, who studied at St John’s college, Oxford, included extracts from Othello and Hamlet in his large miscellany (described in the Catalogue of Early Literary Manuscripts, BL Add MS 22608, circa 1640).

Furthermore, the compiler noted that an excerpt from Romeo and Juliet on page 359 (column 705) was used in a sermon preached in 1620 and 1621 by Nicholas Richardson, of Magdalen College, at the University Church, St Mary’s. This allusion, along with the moral topics discussed in the selections of plays, might indicate that the compiler intended to use this material in similar ways. Wright, a clergyman himself, seems to have collected dramatic material with a view to use it “as rhetorical primers for his own sermons” (Kirsch, 260). The amount of religious literature present in the manuscript could also mean that the compiler read theology, and the many references to Oxford (such as the list at the end of the collection of the most famous writers of the university), and the abundant presence of works by contemporary Oxford men support the hypothesis that the compiler was based at Oxford. Because the manuscript “was handed down at Brasenose from principal to principal,” as pointed out in the Summary catalogue entry (number 28 (32547), volume 6, page 163), it has long been suggested that Samuel Radcliffe (principal from 1614 to 1648) could have potentially been the compiler of this commonplace book. Coatalen, however, has shown by comparing the hand of this manuscript with documents known to be by Radcliffe that this attribution is only “a myth” (120).

C. B. Heberden, the principal of Brasenose College, Oxford, presented the manuscript to the Bodleian Library on April 30, 1898 (as noted in the Summary Catalogue entry number 28 (32547), volume 6, page 163). The original dating of this manuscript is uncertain, but as suggested by Coatalen, the reference to Robert Baker’s 1616 Bible serves to establish a date before which the collection could not have been written, while the latest work mentioned here was published in 1623. The fact that the dramatic extracts occurred on consecutive pages, and that Othello was the last play to be published in 1622, could suggest that these extracts were copied shortly after that year.

Guillaume Coatalen offers a fuller account of the manuscript in his article “Shakespeare and other “Tragicall Discourses” in an Early Seventeenth-Century Commonplace Book from Oriel College, Oxford,” where he also provides a transcription of all dramatic extracts found in the manuscript (which will also be available online on DEx: A Database of Dramatic Extracts).

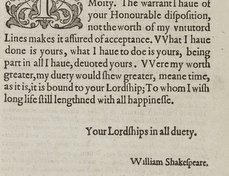

[Image 1: p. 355]

[col. 697]

Ribald. This was at the first Rabod

as yet in the Nertherlands it is asea, where

hence both (we and the french) hauing taken

the name haue sence that varyed it both

in ortography and sence. It was the proper

name of Rabod a heathen King of ffreis

land, who being instructed in the faith

of christ by the godly Bishop vltran faithfully

promised to be baptized, and appointed

the time and place, where being come

and standing in the water, he asked of the

Bishop where all his forefathers were that in

former ages were deceased? the Bishop answer=

ed, that dying without the true know=

ledge of God &c they werein hell: then the

Rabod I hold it better and more praise-

worthy to go with the greater multitude

to hell, then with your few Christians to

heauen; and therewithall he went out of

the water unchristned; and returned both

to his wonted idolatry and to his euill life

notwithstanding the good admonitions of the

Bishop and an euident miracle which (through

the power of god) the said Bishop wrought. He

was afterward surprised with a sodaine and

unprovided death anno 720 and his very

name became so odius through, his wicked

nesse, that it grew to be a tale of reproch

and shame and hath so continued euer since

so do the Papists perswade that our ancestors relli=

gion is the truest

D[?]rabb in the old Teutonic language is the

lees filth and dreges remaining in the bot-

tome of vesells.

the tongues of dying men Inforce attention

like deep harmony where words are scarce

they are seldome spent in vaine for they

breath truth that breath their words in

paine. He that no more must say, is listned more

Then they whom youth and ease hath taught

to gloze, more are mens ends markt then

their liues before. The setting sunne and musick

at the close. As the last tast of sweets is

sweetest last Writ in remembrance more

then things long past. UlF, Usbhfekz

pg Skdibse Uif tfdpoe. cz Tiblftqf

bsf 4o. page 68

morientis hominis loquela verissima

supplant the Irish Rebells those roughheaded

kernes Which liue like venome where no

venome else But only they haue priuiledge

to liue.

[col. 698]

each substance of a greife hath twenty

shadowes, Which shew like greife it self, but

are not so: For sorrowes eyes glazed, with

blinding teares Deuide one thing entire to

many obiects.

great men imitate / unskillfull statuaries who

suppose In forging a Colos.. if they make him

stroddle enough, stroote, and look big and gape

their work is goodly, so our tympanous statists

(In their affected grauity of voice, sowerness of

countenace, manners cruelty, Authority, wealth,

and all the spawne of fortune) think they

beare all the kingdomes worth before them yet

differ not from their Colosick statues which

with heroique formes without orespread within

are nou[h]t but mortar flint and lead

man is a torch borne in the wind; a dreame

But of a shadow summ’d with all his substance

as great seamen using all their powers and

skills in the Neptunes deep invisible paths in tall

ships richly built and ribd with brasse. To put

a girdle round about the world, when they

haue done it, comming neere their Hauen Are

glad to give a warning peece, and call A poore

staid fisherman that neuer past His countryes

sight to waft and guide them in: So when we

wander farthest through the waues of glassy

glory and the gulfes of state Topt with all

titles, spreading all our reaches As if each priuate

arme would spheare the world We must to vertue

for her guide resort, Or we shall shipwrack in

our safest port DWttz Eo BNCpRt CZ

H: DIB Gnbo: 4o page 70

god…... is that true guide

There is no second place in Numerous state

that hold more then a Cypher: In a King

All places are containd. his words and looks

Are like that flashes and the bolts of Ioue:

His deeds inimitable like the Sea

that shuts still as it opes, and leaves no tractes

Nor prints of president for poor mens factes

The French Court is a meere mirrour of confusion

the King and Subiect, Lord and euery slaue

Dance a continuall hay

that (like a Lawrell put in fire

sparkled, and spit, did much much more than scorne

that his wrong should incense him so like chaffe

To go so soone out; and like lighted paper

Approoue his spirit at once both fire and ashes

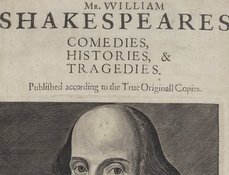

[Image 2: p. 359]

[col. 705]

Forget not mother what are children

Nor how you haue gron’d for them, to what loue

they are borne inheritours, with what care kept

And as they rise to ripeness, still remember

How they imp out your age, and when time calls you

That as an Autumne flower you fall, forget not

How round about the hearse they hang like penons:

Tis almost morning I would haue thee gone

And yet no father then a wantons bird,

That lets it hop a little from his hand,

Like a poore prisoner, in his twisted gyues,

Then with a silken thread plucks it back againe

So iealous louing of his liberty. Tragedy of

Romeo and Iuliet .4o: pag: 84:

radius p(er)uenit proi(n) cadere

this Mr Richard^son College Magdalen inserted hence

into his Sermon, preached it twice at Saint Maries

1620.1621. applying it the to gods loue to

his Saints either hurt with sinne, or aduersity

neuer forsaking them.

- a man I knew but in his euening

- the storme in which sad parting blow

- leuell him a way to repentance

- shame blast your black memory. Scornfull

Lady: Comedia by Francis Beaumont: 4o

page 70: 1616

M[omford]. He in all things rich, in his mind

E[ugenia]: Why seeks he me then?

M[omford]. To make you ioynt partner with him in all

things; and there is but a little partiall difference

betwixt you that hinders that universall ioy where

the bignesse of this circle held too neere our

eye keepes it from the whole spheare of the

sunne but could we sustaine it indifferently be-

twixt us and it, it would then without check

of one beame appeare in his fullnesse.

TRP HGMFT HppTDBgg Comedia 4o:

page 80: 1606

- nor in her tender cheeks

the standing lake of impudence corrupts

shee thus to change? frailty thy name is wo-

man. USBHFEK pg IBNMFU: 4o:

pag: 100. by Shakes TIBLftqfBRE.

1605

[col. 706]

I do know

When the blood burnes, how the prodigall soule

Lends the tongue vowes; these blazes daughter

Giuing more light then heate extinct in both

Euen in their promise, as it is a making

you must not take for fire--

- thou hast been

One in suffring all, all as that suffers nothing

A man that fortunes buffets and rewards

Hast tane with equall thanks; and blest are those

whose bloud and iudgement are so well comedled,

That they are not a pipe for fortunes finger

To sound what stop she please —

— incest — such an act — forgetting of former husband

That blurs the grace, and blush of modesty,

Calls vertue hypocrite, takes of the rose

From the faire forehead of an innocent loue

And sets a blister there, makes mariage vowes

As false as dicers othes --

—an earnest coniuration fro’ the King to th’King,

As loue betwixt them like the palme might flourish,

As peace should still her wheaten garland winne

And stand a Comma’ tweene their amities—

a quiet conscience is a iewell of iewells

the price of it is far aboue the pearle

neither can it be valued with the wedge

of fine gold. But this is a flower which

groweth not in the gardens of Rome, no

not in Beluedere the Popes paradise: for

there is no religion in the world which can

pacify the troubled conscience, but that only

which teacheth the penitent spirit the remis-

sion of his sinnes, and an infallible certainty

of his saluation by the merits of Ies Christ

apprehended by a true and liuely faith and

sealed to the sanctified soule by the spirit of

grace. But the present Religion of the Church

of Rome teacheth only a morall, coniecturall

and fallible. Bell de iusti... : l.3.(.2.243.) That

it is uncertaine certainty which must needs

plunge the poor soule in a 1000 perplexities

The consecration of the Bishops of the

Church of England with their succesion &c.

By Francis Mason. folio: page 278 . 1613

[Image 3: p. 375]

[col. 375]

I will with iealousy blind him—So will I

turne her vertue into pitch And out of her

owne goodnesse make the net That shall

enmesh them all. URBHfEX:pg:PUff

mmp:&t by w. shakespeare. pag: 100. 4°. 1622.

=eta typia

—did he liue now

This sight would make him do a desperate turne,

Yea curse his better Angell fro’ his side

And fall to reprobation.

desperatio ab afflictionis

Written by Beatrice Montedoro

Sources

Guillaum Coatalen"Shakespeare and other 'Tragicall Discourses' in an Early Seventeenth-Century Commonplace Book from Oriel College, Oxford," English Manuscript Studies 1100–1700, 13 (2007): 120–64

Arthur C. Kirsch “A Caroline Commentary on the Drama,” Modern Philology, 66 (1968): 256–61

The Shakspere Allusion-Book: A Collection of Allusions to Shakespeare from 1591 to 1700, ed. by John Munro, rev. edn., 2 vols. (London: Chatto & Windus, 1909)

A Summary Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford Which Have Not Hitherto Been Catalogued in the Quarto Series, ed. by Richard W. Hunt and Francis F. Madan, 7 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1895–1953)

Last updated June 9, 2020