Terms of use

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, has graciously contributed images of materials in its collections to Shakespeare Documented under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. Images used within the scope of these terms should cite the Bodleian Libraries as the source. For any use outside the scope of these terms, visitors should contact Bodleian Libraries Imaging Services at imaging@bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

Copy-specific information

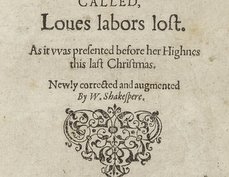

Title: A pleasant commodie, of faire Em the millers daughter of Manchester.

Date: Lond. for T.N. and I.W., [1592?]

Repository: Bodleian Library, Oxford University, Oxford, UK

Call number and opening: Mal. 208 (5), title page

View online bibliographic record

Fair Em is an anonymously written play that at various points since the mid-seventeenth century has been attributed to Shakespeare. The first edition of Fair Em, the Miller’s Daughter of Manchester is an undated quarto presumably printed by John Danter, whose printers’ device suggests a probable date of circa 1591–93 (STC 7675). The first edition was never entered into the Stationers’ Register and bears no authorial attribution.

Although no record of performance survives, the title-page advertises the play as “sundry times publicly acted” in London by Lord Strange’s Men. From November 1589, Strange’s Men are known to have played in London at the Cross Keys Inn and then the Rose, with occasional appearances at court, until September 25, 1593, when the company became Derby’s Men upon their patron’s succession to the earldom. The absence of entries for the play in Philip Henslowe’s records of performances at the Rose Theater suggests that the Strange’s Men retired Fair Em from their repertory by February 1592, further limiting the date of likely first performance to 1589–91.

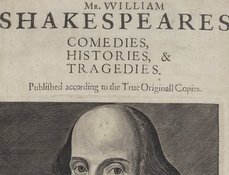

The play’s anonymity has fueled speculation about its authorship, with no fewer than seven candidates proposed: Edward Alleyn, Robert Greene, Thomas Kyd, Thomas Lodge, Anthony Munday, Robert Wilson and William Shakespeare. Until recently, scholars believed Edward Phillips’s dubious attribution of Fair Em to Robert Greene in his Theatrum Poetarum (1675) to be the earliest attempt to identify the play’s author. However, Peter Kirwan established that Fair Em’s inclusion with seven other plays in a no-longer-extant volume inscribed “Shakespeare, Vol. 1” and bound in the 1630s in the Royal Library of Charles I predates Phillips’s attribution by some 30 years. Edward Capell, who had the volume rebound when it passed into the collection of David Garrick, listed Fair Em in his ten-volume edition of Shakespeare’s works, Mr William Shakespeare his Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1768), as one of seven plays “that are upon good grounds imputed to him” (1:10) and which may have been written early in his career (1:16). Even so, Capell excluded Fair Em from his edition.

It was not until the nineteenth century that serious attempts to associate the play with Shakespeare emerged, beginning with Ludwig Tieck’s Shakespeare’s Vorschule (1829). Tieck included Fair Em on the basis of the Royal Library volume (which he incorrectly believed to have belonged to Charles II) and, following Capell, treated the play as Shakespearean juvenilia. Perhaps Richard Simpson’s attribution of Fair Em to Shakespeare in his two-volume School of Shakspere (1878) is the most ambitious – and strained. According to Simpson, Fair Em is not only a “satire upon Greene, and in a measure a parody of some of his works” (2:339), a Shakespearean riposte in a long-standing and bitter rivalry between Greene and himself, but also an elaborate allegory about the professional theater in which characters in the play are thinly veiled references to contemporary playwrights and actors. Simpson states:

Both branches of the plot refer to events in the history of the stage. William the Conqueror is William Kempe, who in 1586 went as head of a company to Denmark to espouse the princess Blanch, that is, to make himself the master of the Danish stage. But on his arrival there he was more struck with the chances of another career, and very soon eloped to Saxony, to turn his histrionic talents to more account there. Mounteney and Valinford are two of his company whom he would have taken with him, but who preferred to stay behind, and contend for the prize of the Manchester stage, which Lord Strange’s players were then bringing into repute. And the second part of the plot carries on the history of this Manchester contention. The windmill, with its clapper and its grist, is the type of the theatre; the wind is either the encouraging breath of the audience, or the voice of the actors, the clapper the applause, and the grist the gains. The miller’s daughter is the prize; he who wins her bears the bell as play-wright. (2:373–74)

In Simpson’s allegory, Manville stands for Greene, Mountney and his “highflying rodomontade” for Marlowe, and “plain-spoken and homely” Valingford for Shakespeare (2:374–75). Simpson’s attribution has been all but universally dismissed by Shakespeare scholars. Surprisingly, Simpson did not supplement his reading of Fair Em with potentially relevant anecdotal evidence. An entry in John Manningham’s diary for 1602 records an amusing story in which Shakespeare, overhearing Richard Burbage arrange to meet a woman for a tryst after a performance of Richard III in the titular role, beds the woman before Burbage arrives, boasting “William the Conqueror was before Richard III.” Although the joke may simply be a pun – Manningham’s entry ends with an explanatory “Shakespeare’s name William” – it may also be an acknowledgment, as Roslyn Knutson suggests, that Shakespeare may well have played the part of William the Conqueror in Fair Em some years earlier (59). As tantalizing a possibility as it may be, Shakespeare’s possible performance as William the Conqueror in Fair Em is not evidence of his authorship.

The unsettled authorship of Fair Em has allowed theatrical productions to capitalize on the play’s possible Shakespearean connection. The first modern revival of Fair Em was directed by Phil Willmott for The Steam Industry at the Union Theatre, Southwark, from January 8 to February 9, 2013. Advertised as being “by” or “sometime attributed to” Shakespeare, Willmott interpolated lines from Henry the Sixth, Part Three into his adapted script. Two North American productions of Fair Em followed. In November 2013, the Oxford Ensemble of Shakespearean Artists at Oxford College, Emory University staged two performances of Fair Em at the Tarbutton Theater, and Tom DuMoniter directed a production of the play at the Blackfriars Playhouse in July 2014 as part of the American Shakespeare Center’s Theater Camp.

The first edition of Fair Em only survives in two copies. The copy shown here, previously owned by Edmond Malone and now at the Bodleian Library, is complete; the other surviving copy, previously owned by Henry Oxinden of Barham, Kent (1609-1670), now in the Elham Parish Library, Canterbury Cathedral (shelfmark Elham 386) is incomplete. Fair Em also survives in a second edition, set using the first as copy, printed by John Haviland for John Wright in 1631 (STC 7676). The STC lists numerous holdings of the second edition, but like the first, it was never entered into the Stationers’ Register, and bears no authorial attribution on the title page.

Written by Brett Greatley-Hirsch

Sources

Standish Henning (ed.), Fair Em: A Critical Edition. New York: Garland, 1980.

Brett D. Hirsch and Janelle Jenstad, “Beyond the Text: Digital Editions and Performance.” Shakespeare Bulletin 34.1 (2016): 107–27.

Peter Kirwan, Shakespeare and the Idea of Apocrypha. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Roslyn L. Knutson, The Repertory of Shakespeare’s Company, 1594–1613. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Lawrence Manley and Sally-Beth MacLean, Lord Strange’s Men and Their Plays. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Martin Wiggins, with Catherine Richardson, British Drama, 1533–1642: A Catalogue, vol. 3, 1590–1597. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Will Sharpe, “Authorship and Attribution.” William Shakespeare and Others: Collaborative Plays. Ed. Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, with Jan Sewell and Will Sharpe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 643–747.

Last updated March 6, 2018