Terms of use

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, has graciously contributed images of materials in its collections to Shakespeare Documented under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. Images used within the scope of these terms should cite the Bodleian Libraries as the source. For any use outside the scope of these terms, visitors should contact Bodleian Libraries Imaging Services at imaging@bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

Copy-specific information

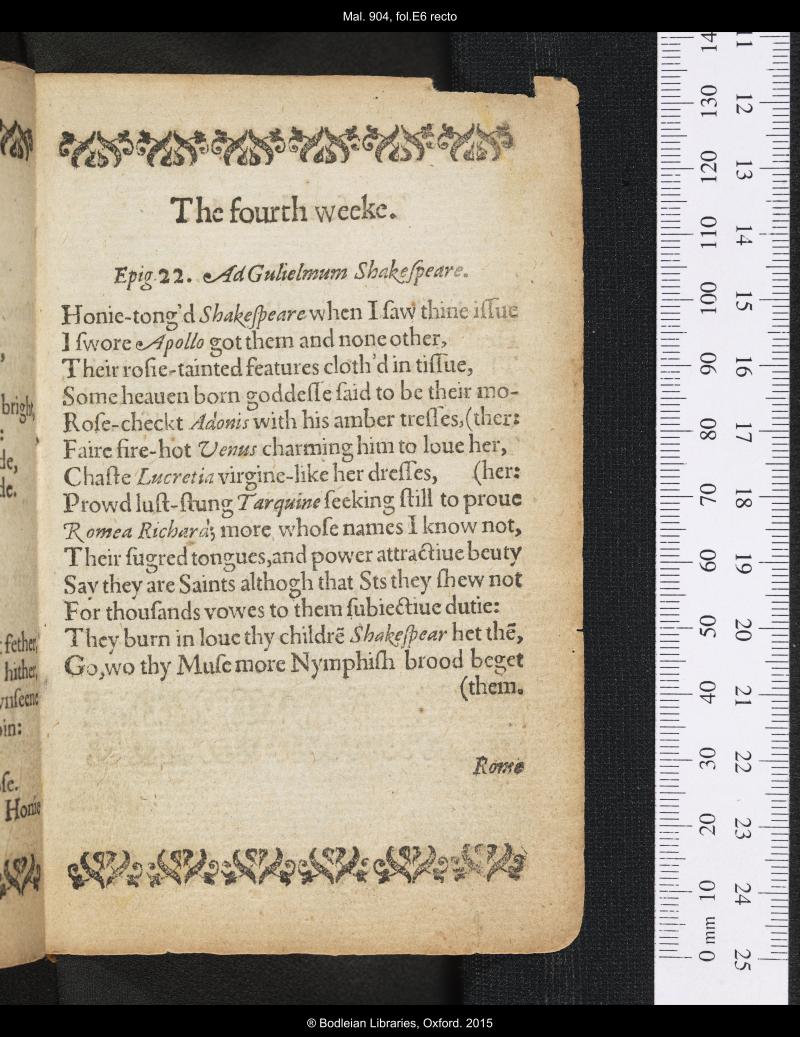

Creator: John Weever

Title: Epigrammes in the oldest cut, and newest fashion.

Date: Lond. V.S. for T. Bushell, 1599

Repository: Bodleian Library, Oxford University, Oxford, UK

Call number and opening: Mal. 904, fol. E6r (epigram 22)

View online bibliographic record

Adam G. Hooks, "Epigrams in the Oldest Cut: critical responses and allusions to Shakespeare and three of his works," Shakespeare Documented, https://doi.org/10.37078/638.

Bodleian Library, Mal. 904. See Shakespeare Documented, https://doi.org/10.37078/638.

John Weever’s Epigrammes in the oldest cut, and newest fashion was published in 1599. Weever began his career as an aspiring poet and literary observer at Cambridge, where he was the student of William Covell at Queen’s College. Covell’s Polimanteia (1595) includes one of the earliest references to Shakespeare in print, and Weever shared his mentor’s interest in Shakespeare’s poetry. Weever eventually made his way to London, where Epigrammes was published. Many of the Epigrammes seem to have been written while Weever was at Cambridge, since they address students and professors, but many others are directed to contemporary literary figures.

Weever’s poem in praise of Shakespeare, given the Latin title “Ad Gulielmum Shakespeare,” is written in the form of a sonnet. This is the only poem in a sonnet form in the Epigrammes, indicating Shakespeare’s renown for this particular poetic form: his sonnets were circulating in manuscript and he had incorporated several sonnets into his printed plays, as well. Weever begins by addressing “Honie-tong’d Shakespeare,” an epithet that recalls Covell’s reference to “Sweet” Shakespeare. Weever includes references to Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, thus confirming Shakespeare’s reputation for a specific poetic style exemplified by his signature poems. Weever also alluded to two other well-known Shakespearean characters who “burn in loue,” Romeo and Richard (presumably the famously seductive Richard III), whose “sugred tongues” and “power[ful] attractiue beuty | Say they are Saints although that S[ain]ts they shew not.” The final phrase alludes to the sonnet that Romeo and Juliet share at their first meeting, in which their playful banter with the religious language of pilgrims and saints leads to a kiss. The Romeo and Juliet sonnet also gave the title to The Passionate Pilgrim collection, which appeared in 1599.

Weever was a dedicated reader of Shakespeare – his Faunus and Melliflora (1600) is an Ovidian poem indebted to Venus and Adonis—but his opinion seems to have quickly changed. In 1601, Weever wrote The Mirror of Martyrs, a rebuttal of sorts to the portrayal of Sir John Oldcastle (in the guise of Falstaff) in the Henry IV plays. Thereafter he abandoned his literary ambitions, and is now best-known beyond Shakespeare studies for his antiquarian work Ancient Funerall Monuments (1631) .

Written by Adam G. Hooks

Sources

E. A. J. Honigmann, John Weever: A Biography of a Literary Associate of Shakespeare and Jonson, The Revels Plays Companion Library (Manchester University Press, 1987).

Adam G. Hooks, Selling Shakespeare: Biography, Bibliography, and the Book Trade (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Last updated May 17, 2020